-

Excerpt from the Chapter “Rex: Discipline”

Rex, unfortunately, was impatient with staying still for long while humans did things to him. Some days he would behave perfectly, and others, he wouldn’t want to do anything. Brushing would elicit small kicks of his back legs and rocking away from the brush. Being on cross ties would make him shake his head and back up as far as he could go, his neck stretched uncomfortably forward and his legs bracing. Sometimes he’d turn himself completely around in the cross ties, with his butt pointed forward and his nose toward the back wall and paw the mat impatiently.

I had a hard time disciplining Rex when he got antsy or frustrated and wiggled around, thrashing his head back and forth. Sometimes if I was already having a bad day, I could smack him and mean it, but most of the time, I just lamely flapped my hand in his face. As everyone at the barn seemed to comment, I “let him get away with things.” I couldn’t punish him effectively. I tried, but I couldn’t keep it consistent. Instead, I’d practice getting very still, hoping to calm him that way. Or I’d just repeatedly guide him back into the normal standing position after he’d twisted himself into a pretzel on the cross ties for the bazillionth time. He never seemed to hate Leslie when she smacked his face or twisted his nose. He just behaved himself. He’d get a meek look on his face after she did it but he’d stand quiet and poised for brushing. I felt inadequate, like a parent who’s been told she’s her child’s friend when he needs a mother. Still, I couldn’t manage a full smack some days. It hung just out of my flapping hand’s reach toward sternness and laughed at me. “Weak,” I heard it say. “Wimp. Pushover.” The same voice from the beginning of my training still haunted me on those days when Rex was especially stubborn. Instead, I worked out small compromises. A rope tied to the fencepost instead of the cross ties and he calmed right down. The next day the cross ties were no problem again. I kept seeking those crevices where I could get a small handhold on peace, even if it meant giving in to Rex once in a while. Because those crevices existed, I never fully developed the sternness I was told made for safe, calm horses. I developed sneaky little ways to give in to a horse without it looking like I was compromising, like someone hacking a trail through underbrush when there was a clear path just to the left of it. I wasn’t sure where I was, but I knew where I was headed. It just took longer and seemed senseless at the time.

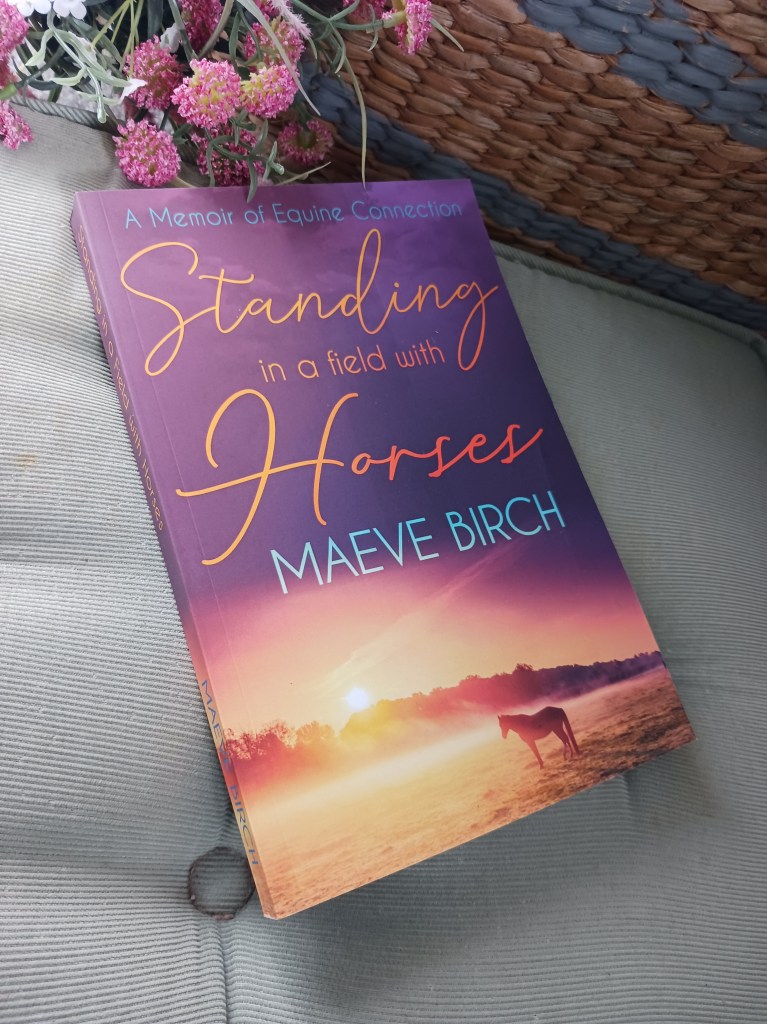

– Excerpt from Standing in a Field With Horses: A Memoir of Equine Connection

-

An Opening

I’ve been busy learning again. It has been a continuous struggle to figure out how to get better at riding horses without compromising on how I want to be in relation to horses. I don’t force a horse to move anymore. It’s so counter to what I’m trying to do in the world that it’s pointless to me if the horse moved because I threatened them. For lesson horses, this sometimes means we’re stuck standing still with an instructor saying words like “don’t let him win.” Words like that unfortunately make me feel things that aren’t conducive to moving with a horse, so we stay stuck and angsty together. I’m at least getting practice in figuring out how to tune unhelpful things out instead of being affected by it. From the outside it looks like I don’t understand the instructions, or don’t have the willpower to implement them. From the inside I’m trying to get back to an inner calm so I can feel for an opening and recognize when the horse offers it. The opening always occurs eventually, even if it’s only wide enough for the horse to shift weight from one foot to the other. It is a door into conversation, and I try to guide us through. I’m still in the process of learning where that conversation goes.

There is a similar opening that happens when someone witnesses something else happening, besides the “ask, tell, demand” that is drilled into most equestrians from the time they first get on a horse. Some small crack occurs when they aren’t told another way verbally, but see it presented in a non-threatening, indirect context. When it has nothing to do with them. When they observe from a safe distance and make their own way over to ask about it. A little opening for a conversation to begin. I’m still learning the nuances of this conversation as well. Humans dislike feeling forced about as much as horses do.

-

Story Snippet: Thoughts on the Herd

You ask how the horses are. I tell you they’re fine. I brushed Spruce. I was able to stand next to Red today. I speak in terns of progress. Activity.

I haven’t told you how peaceful it felt as the cuddly one kept nodding asleep with his nose pressed into my jacket. I haven’t told you there’s a time of day when they drink sunlight like the air itself, lying in the field spread-eagled, rubbing their faces in the dirt with such joy I can’t help but laugh. You don’t know that when I spend hours out there in the cold, I’m watching them spar over the fences. Ten points for the little brown pony who came away with a piece of fly mask in his mouth. He’s dancing through the field with his prize. These are all someone else’s horses. Someone else rides them. Someone else frets over their feed and their vet bills, their ability to jump over fences the right height. I had no introduction to them other than their own, so I know them only by what they told me. This one is stressed a lot. This one has only ever had good things from humans. This one has lost his ability to trust them. They teach me how to be free. Even Red, who has lost his freedom somehow through humans, is more free in his expression and being than I can ever allow myself to be in the everyday. I can’t run laughing through the hallways of my workplace. I can’t throw myself to the ground in the middle of the park, flailing my limbs in the sunlight. Humanity has me bound tight. How does anyone live without their field full of horses? -Maeve Birch, Winter 2018My paperback has increased in price in order to begin making some amount back instead of operating at a loss. I so appreciate you all for being here through my book’s birth and early phases. The eBook remains the same price through both Amazon and SmashWords! Please support this work through giving a review, liking posts, or sharing the book or blog posts with friends and fellow horse lovers. You all mean so much. Thank you.

-

Traveling Around

The book and I are on vacation this week, wandering through the Appalachian mountains again. I took along a few copies to drop off in various places. If you see my book in the wild, it may be that I left it in a coffee shop somewhere!

It feels good to have some time off to relax and be among mountains again. I hope you are able to take some time to relax this summer as well, even if it’s just to stand outside and sip some tea for a bit. Taking in those small moments helps a lot. What small moments do you find comforting or relaxing?

See you in a week!

If you would like to read Standing in a Field With Horses, but have not found a random copy hanging out on a coffee shop bookshelf, see the links on my main page.

-

The Freedom of Waiting

We are paused in the doorway again, the tall nervous horse and I. I’ve pulled him through this opening before. Not this time. He widens his eyes and holds his breath, waiting for something to happen, since things always seem to happen in doorways. Instead, we wait.

It’s seen as a sign of weakness, me walking to the end of the lead rope, asking him to follow, but stopping myself at the end of it and peering back at him without having tugged at the rope. I have instead let it slip through my fingers unimpeded. I’m tethered to him, he isn’t tethered to me here. I’m not the one struggling right now. He looks at me, stretching his neck forward as far as it will go, despite the lack of tension on the halter. “I am trying.” He says with his body, “Look, I am indeed trying.” His feet stay planted in the arena.

I walk back to him, and he mushes his sandy nose into my hair and breathes. He blinks. And breathes. We stand in the doorway together.

After a while I feel a small opening of opportunity. “Ok to go?” I ask.

“Not yet!” His wide eyes insist. His neck tenses, head high. “I’m not ready yet!”

I relax and let the idea float away. “Yes, we’ll wait.”

He sighs and his head lowers an inch.When he tries to distract himself by playing with the dressage whips and brushes beside the doorway, I guide his face back to the entryway. We are solving a problem, and that requires doing nothing. Focus on me, on the idea that nothing is happening. It’s just a place. No events need to occur in this place right now.

More waiting.

Finally, another opening. This time he drops his head to the ground and sniffs his way through the doorway. He follows the scent of other horses who have crossed the threshold, perhaps comforted by their ability to pass through. When he walks it’s calm and quiet. I walk with him, the lead rope still hanging slack between us. Don’t mistake this for weakness. Do not. I am giving space enough for a horse to find his own strength and dignity. This is what I want to give to the world. This space, at his speed. Small victories.

Want to participate in the movement towards a more peaceful way of being with horses? We have an Instagram! @MaeveBirchBooks. Share your story, comment on posts, and find others working with horses peacefully. You can also find my memoir, Standing in a Field With Horses on Amazon and Smashwords

-

Story Snippets: Flora

I barely mentioned Flora, the oldest mare at the rescue, in my memoir. Though I didn’t work with her often, Flora was a wonderful dark bay with a generally pleasant personality, aside from a few quirks. She had a terrible fear of clippers, whips, and fly masks, and grumpyness about picking her feet up. She wasn’t dangerous about it anymore, but she never voluntarily lifted her feet. Unlike my horse friend Spruce, who eventually lifted his hooves on his own once he learned that I was gentle with them, Flora’s hooves stayed firmly on the ground. Unfortunately her hooves were an absolute mess most of the time, due to several health issues. Soft, peeling frogs (the middle, rubbery part of the hoof), crevices which got continuously infected with thrush, heel bulbs that didn’t grow in like they should, cracks and warping. To be honest, hoof picking was probably painful for her. I was still tasked with cleaning them out and medicating them along with all the other hooves in the barn. I tried talking with her about her hooves, explaining as best I could that it was helpful for me to clean them out. I picked out the crevices as gently as I could. Still, with one front hoof in particular, I needed to quite forcefully squeeze the leg tendon to get the hoof off the ground. She’d flail it around if I didn’t wedge it against my own knee while picking, and then slam it back down as hard as she could the first chance she got. None of the other hooves meant as much to her as that one. She was very protective of it. I tried getting her to lean on the wall, thinking maybe it was pain in her other legs keeping her from lifting it more willingly. That didn’t work either. Finally I asked the barn owner why Flora specifically objected to the front left hoof being picked up. “Ah, that one a volunteer once thought they were picking out a rock and they dug in so hard they took out a big chunk of her frog . She was bleeding all over the place. They felt so bad about it. But that’s why she won’t let most people pick it up.” The knowledge didn’t make it any easier to pick her foot out, but it did tell me that it wasn’t me imagining things or making excuses for that hoof being harder to work with. It was a behavior with a real cause. There were most likely other real causes for her fear of fly masks. There are real, legitimate causes to all horse behaviors that seem “naughty” or aggressive. Something happened to them to cause them to be that way. Sometimes we never know what that cause is, but it doesn’t make it less real. Sometimes you’re not the problem, and neither is the horse. It’s just something that happened to them. The memory of fear or pain.

Read more about the horses in my memoir, Standing In a Field With Horses, available on Amazon and SmashWords.

-

Story Snippets: Beating the Rain

I thought I might make the next few blog posts some small story snippets from my time in Field Board that didn’t quite make it into the memoir.

The first is a visit to Red’s field during the early summer, right about this time of year four years ago. I was standing out in the field with the herd, walking along step by step as they swung their way from one end of the field to the other. The wind was picking up and it felt like rain, but there was no thunder to be heard, so I opted to stay in the field until the rain actually showed up.

I mention in the book that Red didn’t like being out in storms. I could never tell whether this was because he disliked getting wet or was afraid of the thunder and lightning. I know there have been pasture accidents where horses are struck by lightning, so maybe Red witnessed this at some point. It’s also possible that he was brought in every time it stormed when he was younger, so he associated storms with being under shelter. Who knows.

He was chancing it along with me this time. They were all still grazing when it started to sprinkle a bit. He didn’t look up as I began plodding back over towards the run in, not wanting to leave the peaceful field. I had no raincoat with me. I didn’t want to drive home soaking wet.

Suddenly the drops got much bigger.

“Oh no.” I whispered under my breath.

I heard the deluge hit the tin roof of the main barn at the other end of the property.

“OOOOH NO.” I wailed. I began sprinting towards the run-ins.

From behind me I heard the pounding of heavy hooves join the pounding of heavy rain. As I hit the paddock fence and practically vaulted over it, Red and Matteo came tearing around the corner and through the open paddock gate. We all staggered into the run-in at the same time, seconds before the deluge, snorting and blowing out big sighs at beating the rain.

“Not too bad for wimpy human legs.” I thought to myself.

The rest of the horses had stopped at the fenceline and stood staring at us through the downpour, rivulets of water running off their backs and down their faces. I’m not sure I’ll ever know why some horses detest getting wet and others don’t mind it. Matteo would probably have been right out there with the rest of them if he weren’t such good friends with Red. As for me, I made it back to my car only slightly damp after the rain stopped. A successful visit.

Read more adventures with Red, Matteo, and other horses I have known in Standing in a Field With Horses.

-

Guilt and Smoke

The past two days have been full of wildfire smoke here on the east coast of the US. What at first seemed like a weird orange sunrise turned into an all-day warning to stay indoors and watch through closed windows as the neighborhood was enveloped in a thick haze. Horses, unfortunately, didn’t have the option to go indoors or wear a mask outside. Those at the barn with pre-existing breathing problems were given their inhaler or nebulizer treatment throughout the day, and no one was ridden. Hopefully this round of smoke has moved on, but the lung irritation from so much smoke will continue for a week or two.

As for me, my allergies extend to wildfire smoke, it seems. I woke up yesterday with a headache, strange feeling in my chest, and an exhaustion that wouldn’t go away with caffeine. Even though I stayed in my house, I was still struggling. I called off of work because I couldn’t concentrate through my symptoms. I felt guilty, like I was making too big of a deal out of it. Why could everyone else cope and I couldn’t? It didn’t change my symptoms, though. Feeling guilty about them didn’t help me get rid of them.

Sometimes I still struggle with feeling guilty about not making horses work too, like it’s some failing on my part that I stop when they’re telling me something is painful when others would push them through it. One of the horses who used to breathe heavily and cough while in lessons was one I was hesitant to make do things. Sometimes I would push him anyway, though, because there were several people who told me that was just normal for him and he got over it once you pushed him through it. He ended up being diagnosed with heaves. He’s one of the horses on a nebulizer this week. He never felt guilty about his symptoms. He just displayed what was happening with him, and tried his best to create a scenario where he would feel better. It was the humans feeling guilty about his “lack of work ethic” that caused the issue. Feeling guilt for not making him work, like we’re conditioned to believe needs to happen for a horse to justify their expense. To avoid embarrassing us.

What if we stopped berating ourselves when we stopped to rest? Would we extend that grace more easily to others? If we felt less guilt, felt less need to justify taking up space in this world, would we feel less pressure to say “you have to work” to the horses in our lives? One can only hope.

Don’t forget to leave a review on Amazon if you’ve finished reading Standing in a Field With Horses. It really helps others to find the book. Thanks so much to those who have left a review already. We are working towards a goal of 20 reviews!

-

Something Else

My mentor and I talk pretty freely with each other at this point about the various energetic and “supernatural” things we encounter in our day to day lives. Part of an animistic worldview is that non-physical spirits are about as common as physical ones, just sort of overlayed on top of the physical, most of them minimally able to interact with it. So when my mentor told me that the mares were refusing to enter their run-in shelter the other day and she had seen what looked like heat-shimmer hanging around in it, I spoke about it the same as if she’d spied a fox in the building. Something Else was in there, even if we couldn’t pinpoint what it might have been.

“What did you do?” I asked, intrigued.

“Well, I told it sternly that it needed to leave because it was frightening the mares. It left.” She stated. “The mares asked me to make sure it was gone and then once I’d reassured them, they went right in for breakfast.”

Another volunteer, less accustomed to the talk of non-corporeal beings and chatty mares, held up a hand in protest. “Wait, they talked to you? Like you heard them say stuff?”

My mentor and I exchanged a hesitant glance, and I made a noncommittal sighing noise.

“It’s not exactly a voice, per-se” she tried to elaborate. “It’s like a thought, or a feeling, but not quite. It’s hard to explain.”

We went back to our respective barn chores, but the conversation stuck with me. Why is it so hard to explain what happens when we “hear” a communicated thought or feeling from a horse? Why is it so hard to describe energy and how that feels or acts when it’s moving around or through us? I struggled with it myself when I was writing my memoir. We only recognize five senses for understanding our physical environment. It’s so difficult to reach for words past that. Even the word “energy” is like a stand-in for whatever it is that we are using in Reiki and other energy work. It isn’t a physical thing we can measure, and isn’t part of the electromagnetic spectrum. It’s just Something Else. Working with that something-ness, like any skill based on the senses, takes time and practice to learn. A quiet brain to “hear” with, and persistence to obtain an ear for the peculiar and intricate music of “Something Else.” I firmly believe that anyone can learn to read and manipulate energy, given time and practice. I definitely understand why people don’t try, though. It’s not exactly a dominant worldview or practice in our current western culture. Horses do tend to pull you into it, though, if you stand with them long enough.

Get pulled into a great read with my memoir, Standing in a Field With Horses. Available on Amazon, Smashwords, and several other online bookstores! Belief in spirits and animal communication completely optional.

-

Ponderings

Things have been really chaotic on all fronts this week, so this blog post may be a bit scattered. Things at work made me realize over again that not everyone is going to like me. Sometimes it’s not for any good reason. Just as I can clash with someone else’s personality, so they can clash with mine. At work sometimes there’s no avoiding someone who dislikes my personality. Instead we must figure out some way to exist in proximity to each other while causing the least amount of angst. Some days that’s difficult.

Things at the barn made me realize that horses have this same issue. If horses are kept in the same field together, they must find some way to live with each other that causes the least amount of angst possible. Horses are not humans, though, and may find different ways of solving this problem than we do. The mares don’t particularly like each other in the upper field at the barn. One kicked another hard enough to require a trip to the vet. Why they do this I still don’t understand. Maybe I never will. I do know it’s expensive and stressful when they solve their problems like this.

I never want to appear like I have things all figured out, or that I’m at the final destination of what I believe to be true about horses. Lately I’ve realized that I’m a bit stuck in understanding the threshold of frustration in a horse that is still ethical to push. What is tolerable and fair, versus damaging and unfair? I don’t quite know yet. I’m asking mentors for help and trying to work through it. I hope you’re working your way through things too, whether at a crawl or a giant leap. As long as we’re still wondering and listening and searching, I think it’ll turn out ok.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.